Steve Whitaker, Features Writer

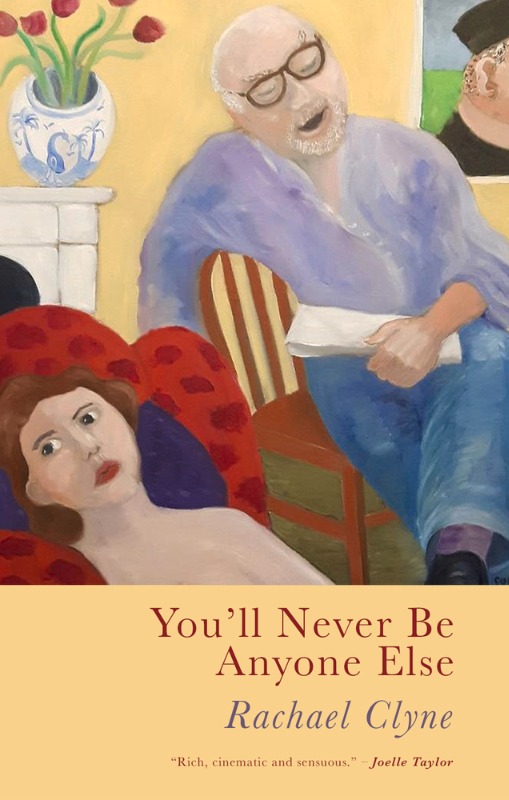

Witnessing The Burn: You'll Never Be Anyone Else By Rachael Clyne

...she is astonishingly insightful as to the prevalence of complacent racism...

Striking a balance between powerful institutional blandishments and an inherent inclination for independence, the poet adopts and reverses the traditional role of the mythical Golem, to explore her own stifling relationship with a family whose traditions demand obeisance. The ‘Girl Golem’ whose ‘assimilation ticket’ meant finding ‘a nice boy and mazel tov - grandchildren!’ didn’t fit, was a ‘hotchpotch golem, a schmutter garment’, ‘trying to find answers / without a handbook.’That Clyne frequently uses Yiddish terms in her poems, and includes a helpful accompanying glossary, underwrites both an acceptance of the culture that made her, and an ambivalent affection for those who continue to shape her thinking. Making, like Scots-Jewish poet David Bleiman, constructive wholes out of a prolix confusion of heredities, her poems may fall short of the ‘trebbling’ or hybridizing of dialects, but they do create a robust idiolect, a personal slant on her own development that is highly original and fully emotionally charged.

The girl who is parcelled off to ballet class, to develop ‘posture and grace’ suitable to attract the ‘right kind of boy’, will only be dumbstruck when her own son and daughter betray the rubric

And there is a debt. The poet’s sense of her ancestry is acute. The centrality of constructive labour and continuity to self-worth, to the feeling of community belonging, yields some novel use of metaphor. Describing her immediate relatives in terms of pieces of furniture, Clyne makes a solid ‘Three Piece Suite’ of the family unit, except that her narrator’s own memory is riven by the presence of other suggestions, rendered self-explanatory in what R. D. Laing referred to as the gangsterish tendencies of domestic drama:‘Between chair, ironing board and pouffe,

I, their tailor’s cushion, bristle with pins.’

The mother and father who take pleasure in ‘claiming’ the daughter’s appearance and attributes – ‘my smile, says mum. / My nose, says dad.’ – demand a vicarious share in ownership, and elicit, instead, a reflexive desire in the teenager to bugger off, ‘eyes fixed ahead’. (‘Our Usual Walk’). So far, so normal; but the cultural rootedness of both physical and emotional idiosyncrasies is pervasive, more still the silent insinuation of inherited memory. The self-lacerating stereotypes of ‘White/Other?’, and ‘The SCHNOZZ’ describe the blindness of the uninformed, the complacent cruelty of ignorance, and the mechanisms of denial that protect the juvenile need for assimilation. Clyne’s opening sestet in the latter is direct, compact and brutally frank, combining the hooter archetype with the culturally ingrained assumption of semitic greed, as cash is hoovered up like a line of cocaine:

‘No cute buttons for us.

No retroussé

just a big fuck-off hook

with wind tunnel nostrils

sucking up everyone’s money

and stuffed with your Zio conspiracy bogies’

Clyne is brave to venture into territory that is at once unsettling and redolent of formative control, and she is astonishingly insightful as to the prevalence of complacent racism, which is less meaningful to those who are not victims of it. Scoping the plains of Ukraine for her ancestors, she traces a long temporal line of anti-semitism to the shores of the Black Sea, and finds, in the ‘perky blue’ uniforms and glasses of tea on the comfy train, the prefabricated lie of exile that conceals an earlier truth of pogroms and forced migration:

‘Through the window, I see grandma leaving this land,

a baby in her arms, her husband in his fine astrakhan hat.

This is how migrant tales become holiday destinations,

how debts are paid and how her roof became my ground’. (‘Leaving Odesa’)

The sense of continuity, of consanguinity, is as palpable as the whisper of plus ça change echoing around the carriage.

A broaching of cultural borders is achieved with pugnacious elan; the negotiations of her earlier years lead not to compromises, but to hard-fought and refreshing sureties about identity and sexuality. The child who role plays by instinct, learning not to conform naturally – ‘Given the chance, we’d have swapped his pants / for my dresses’ (‘Proposal’) - is a prelude to the later, unrelated, figure who can now laugh in hindsight at the circumscribed weirdness of parental gender expectation. The girl who is parcelled off to ballet class, to develop ‘posture and grace’ suitable to attract the ‘right kind of boy’, will only be dumbstruck when her own son and daughter betray the rubric:

‘What she doesn’t plan for, is her daughter

joining the 5th Regiment Royal Artillery –

or for her son to take amphetamines

and run off with the lad from the chippie.’ (‘Susan Expects to Be Admired’)

Clyne’s exquisite sense of contrapasso, as well honed as Claire Askew’s elsewhere, is achieved in the final quatrai...

Susan’s children’s unwillingness to conform to the demands of convention is a mirror to Clyne’s own, yet the witty schadenfreude of the poet’s delivery, here, is a bitter postscript to an earlier form of obedience to cultural hegemony. For the narrator’s voice, across much of this fine collection, is cognizant of the shadow of emotional abuse, of the controlling male gaze, and of physical violence. Rendered at one remove by the skilful use of extended metaphor and third-person observation, Clyne restores tenure in narratives of insidious dominance. While the returning Golem figure is subsumed, drifting directionless in a desert of matrimony and lacking the ‘fixed horizon’ of identity (‘Girl Golem is Stranded in Marriage’), the concrete facts of her mental incarceration are iterated painfully in pastiches of sporting endeavour:‘It’s his indoor sport she dreads

when he empties his eyes, sharpens

his hand skills. Swift upper cut, slap, grab –

his trophies scrawled across her face.’ (‘Indoor Sport’)

The empty eyes roll in psychopathic detachment, like a shark in attack mode, and demand no less than a skewering corrective. Clyne’s exquisite sense of contrapasso, as well honed as Claire Askew’s elsewhere, is achieved in the final quatrain of the poem immediately preceding, as the ship in the bottle of subjection and enchainment meets its own Trafalgar:

‘He places her on an ornate shelf, where he

can keep an eye on her graceful lines.

she dreams of catching an evening tide

or finding a small but effective hammer.’ (‘Full Sail’)

Rachael Clyne’s sentiments are admirably controlled here and throughout her collection. The wielding of Enoch's toffee hammer is a fitting preface to, if not a precondition of, the independence of thought and action that will proceed under full sail towards the resolution of the final pages of her book; a neat, unexamined, counterpoint to the full-throttled sexual abuse delineated in the shape of a penis in the horrific concrete poem ‘Take the Medicine’, which concludes like a rapist’s demand - ‘now take it / take it.’

For this poet is never less than honest, or viscerally frank, in a realm of antithesis and confusion of identity. An open-hearted paean to tolerance, Clyne’s poems encourage a belief in the polychromatic prism of culture and taste in a landscape that refuses to keep up:

‘DMs or lippie – just come.

Spectrums welcome.

Are you nearly there yet?

We’ll wait – don’t fret’ (‘Birls and Goys Come Out to Play’).

In fact, any sense of resolution resides in an acceptance of not knowing the answers, of celebrating, instead, our place in the moment. The penultimate poem of a profoundly engaging collection gives medicine to the jaundiced, and consolation to experience:

‘Do not mistake your last golden hour

of flame for a new dawn. Witness the burn.

Give thanks. Leave it to curl on the wind.’ (‘Sometime in the next ten years’)

You’ll Never Be Anyone Else is published by Seren.

More information here

More information here